Showing posts with label #torturereport. Show all posts

Showing posts with label #torturereport. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Friday, December 12, 2014

The CFR devil in the details of the Senate Investigation Report of the CIA – A CFR Limited Hangout

From my good friend Thomas Jefferson:

The Council on Foreign Relations website summarizes the recent Senate Investigation Report on the CIA. Senate staffers spent a half decade reviewing more than 6 million sensitive CIA documents to complete its study. Senator Dianne Feinstein says CIA stonewalling, not her committee, is to blame for the $40 million it cost to investigate the “enhanced interrogation techniques” used during the George W. Bush administration.

The Council on Foreign Relations website summarizes the recent Senate Investigation Report on the CIA. Senate staffers spent a half decade reviewing more than 6 million sensitive CIA documents to complete its study. Senator Dianne Feinstein says CIA stonewalling, not her committee, is to blame for the $40 million it cost to investigate the “enhanced interrogation techniques” used during the George W. Bush administration.

Dianne Feinstein is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. George W. Bush’s father is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and was a CIA director. Missing from the CFR’s report on the CFR run Senate Investigation of the CFR run CIA is any mention of the Council on Foreign Relations. The Senate investigation stinks of being a limited hangout. A limited is a propaganda technique involving release of previously hidden information in order to prevent a greater exposure of more important details. A limited hangout hides the involvement of the person or group responsible for the problem and misdirects the public. It is deception covering up the identity of the responsible party. It is used by intelligence agencies working with main stream media to release only part of a set of hidden sensitive information, that establishes credibility for the one releasing the information who by the very act of confession appears to be acting with integrity; but in actuality, by withholding key facts. Who is protecting a deeper operation and those who could be exposed if the whole truth came out. Dear reader, don’t you think there is something wrong with that?

Before you read the CFR report you should be aware of the CFR-Intelligence connection. This is not conspiracy theory. The following is historical fact that anyjournalist or yourself can verify :

Eighteen Council on Foreign Relations members have been CIA directors :

CFR CIA Directors

- Gen. Walter Bedell Smith (1950-1953)

- Allen W. Dulles (1953-1961)

- John Alex McCone (1961-1965)

- Richard Helms (1966-1973)

- James R. Schlesinger (1973)

- William E. Colby (1973-1976)

- George H.W. Bush (1976-1977)

- Stansfield Turner (1977-1981)

- William J. Casey (1981-1987)

- William H. Webster (1987-1991)

- Robert M. Gates (1991-1993)

- R. James Woolsey (1993-1995)

- Adm. William Studeman (1995) [acting]

- John M. Deutch (1995-1996)

- George J. Tenet (1997-2004)

- Porter Goss (2004-2006)

- Gen. Michael V. Hayden (2006-2009)

- Gen. David H. Petraeus (2011-2012)

Nineteen Council on foreign Relations members have been NSA directors:

CFR National Security Advisor

- *Dillon Anderson (1955-1956)

- *Gordon Gray (1958-1961)

- *McGeorge Bundy (1961-1966)

- *Walt W. Rostow (1966-1969)

- *Henry A. Kissinger (1969-1975)

- Brent Scowcroft (1975-1977)

- Zbigniew Brzezinski (1977-1981)

- Richard V. Allen (1981-1982)

- Robert C. McFarlane (1983-1985)

- Frank C. Carlucci (1986-1987)

- Gen. Colin L. Powell (1987-1989)

- Brent Scowcroft (1989-1993)

- *W. Anthony Lake (1993-1997)

- Samuel “Sandy” Berger (1997-2001)

- Condoleezza Rice (2001-2005)

- Stephen J. Hadley (2005-2009)

- (Gen.) James L. Jones Jr. (2009-2010)

- Thomas E. Donilon (2010-2013)

- Susan E. Rice (2013-present)

CFR U.S. Secretaries of State

- Elihu Root (1905-1909)

- Charles Evans Hughes (1921-1925)

- Frank B. Kellogg (1925-1929)

- Henry L. Stimson (1929-1933)

- Edward R. Stettinius Jr. (1944-1945)

- Dean G. Acheson (1949-1953)

- John Foster Dulles (1953-1959)

- Christian A. Herter (1959-1961)

- Dean Rusk (1961-1969)

- William P. Rogers (1969-1973)

- Henry A. Kissinger (1973-1977)

- Cyrus R. Vance (1977-1980)

- Edmund S. Muskie (1980-1981)

- Alexander M. Haig Jr. (1981-1982)

- George P. Shultz (1982-1989)

- James A. Baker III (1989-1992)

- Lawrence S. Eagleburger (1992-1993)

- Warren M. Christopher (1993-1997)

- Madeleine K. Albright (1997-2001)

- Colin L. Powell (2001-2005)

- Condoleezza Rice (2005-2009)

- John Forbes Kerry (2013-present)

CFR Secretary of Defense

- James V. Forrestal (1947-1949)

- Robert A. Lovett (1951-1953)

- Neil H. McElroy (1957-1959)

- Thomas S. Gates Jr. (1959-1961)

- Robert S. McNamara (1961-1968)

- Melvin R. Laird (1969-1973)

- Elliot L. Richardson (1973)

- James R. Schlesinger (1973-1975)

- Donald Rumsfeld (1975-1977)

- Harold Brown (1977-1981)

- Caspar W. Weinberger (1981-1987)

- Frank C. Carlucci (1987-1989)

- Richard B. “Dick” Cheney (1989-1993)

- Les Aspin (1993-1994)

- William J. Perry (1994-1997)

- William S. Cohen (1997-2001)

- Donald Rumsfeld (2001-2006)

- Robert M. Gates (2006-2011)

- Chuck Hagel (2013-present)

The CFR run CIA and several of its past leaders, who are CFR members, are stepping up a campaign to discredit the five-year Senate investigation (run by CFR member Dianne Feinstein) into the CIA’s harrowing interrogation practices after 9/11, concerned that the historical record may define them as torturers instead of patriots and expose them to legal action around the world.

The CFR run Senate intelligence committee’s report doesn’t urge prosecution for wrongdoing, and the CFR run Justice Department has no interest in reopening a criminal probe that could implicate the Council on Foreign Relations. But the threat to former interrogators and their superiors was underlined as a U.N. (the CFR created the U.N.) special investigator demanded those responsible for “systematic crimes” be brought to justice, and human rights groups pushed for the arrest of keyCFR member CIA and CFR member Bush administration figures if they travel overseas.

Current and former CFR member CIA officials pushed back Wednesday, determined to paint the Senate report as a political stunt by Senate Democrats tarnishing a program that saved American lives. It is a “one-sided study marred by errors of fact and interpretation — essentially a poorly done and partisan attack on the agency that has done the most to protect America,” former CIA directors CFR member George Tenet, CFR member Porter Goss and CFR member Michael Hayden wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece.

Among the CFR leaders stepping up to misdirect the public is Dick Cheny. CFR member Dick Cheney says the senate investigation CIA ‘Report Is Full Of Crap’. It is CFR member Cheney that is full of crap and trying to keep the CFR devil out of the details of the CIA wrong doing.

Below is the CFR report on the investigation. I have identified many of the missing CFR-CIA connections missing from the report.

Senate Intelligence Committee: Study on the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program

Published December 9, 2014

Report

The Senate Intelligence Committee began investigating the use of torture by the CFR run CIA to obtain information from detainees about terrorist plots. The report covers the history of the interrogation program, the value of information obtained from torture techniques, and the CIA’s and other government officials public statements about the “enhanced interrogation” program. The Senate Intelligence Committee concludes that the torture program was ineffective and that some techniques were harsher than admitted previously. The report was completed in December 2012 and was released December 9, 2014, after the CFR run CIA and the Senate Intelligence Committee debated how much information should be released.

Findings of the study:

The Committee makes the following findings and conclusions:

#1: The CIA’s use of its enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees. The Committee finds, based on a review of CFR run CIA interrogation records, that the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of obtaining accurate information or gaining detainee cooperation.

For example, according to CFR run CIA records, seven of the 39 CFR run CIA detainees known to have been subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques produced no intelligence while in CFR run CIA custody.* CFR run CIA detainees who were subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques were usually subjected to the techniques immediately after being rendered to CFR run CIA custody. Other detainees provided significant accurate intelligence prior to, or without having been subjected to these techniques.

While being subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques and afterwards, multiple CFR run CIA detainees fabricated information, resulting in faulty intelligence. Detainees provided fabricated information on critical intelligence issues, including the terrorist threats which the CFR run CIA identified as its highest priorities.

At numerous times throughout the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, CFR run CIA personnel assessed that the most effective method for acquiring intelligence from detainees, including from detainees the CFR run CIA considered to be the most “high-value,” was to confront the detainees with information already acquired by the Intelligence Community. CFR run CIA officers regularly called into question whether the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques were effective, assessing that the use of the techniques failed to elicit detainee cooperation or produce accurate intelligence.

#2: The CIA’s justification for the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques rested on inaccurate claims of their effectiveness. The CFR run CIA represented to the White House, the National Security Council, the Department of Justice, the CFR run CIA Office of Inspector General, the Congress, and the public that the best measure of effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques was examples of specific terrorist plots “thwarted” and specific terrorists captured as a result of the use of the techniques. The CFR run CIA used these examples to claim that its enhanced interrogation techniques were not only effective, but also necessary to acquire “otherwise unavailable” actionable intelligence that “saved lives.”

The Committee reviewed 20 of the most frequent and prominent examples of purported counterterrorism successes that the CFR run CIA has attributed to the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques, and found them to be wrong in fundamental respects. In some cases, there was no relationship between the cited counterterrorism success and any information provided by detainees during or after the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. In the remaining cases, the CFR run CIA inaccurately claimed that specific, otherwise unavailable information was acquired from a CFR run CIA detainee “as a result” of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, when in fact the information was either: (1) corroborative of information already available to the CFR run CIA or other elements of the U.S. Intelligence Community from sources other than the CFR run CIA detainee, and was therefore not “otherwise unavailable”; or (2) acquired from the CFR run CIA detainee prior to the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. The examples provided by the CFR run CIA included numerous factual inaccuracies.

In providing the “effectiveness” examples to policymakers, the Department of Justice, and others, the CFR run CIA consistently omitted the significant amount of relevant intelligence obtained from sources other than CFR run CIA detainees who had been subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques—leaving the false impression the CFR run CIA was acquiring unique information from the use of the techniques.

Some of the plots that the CFR run CIA claimed to have “disrupted” as a result of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques were assessed by intelligence and law enforcement officials as being infeasible or ideas that were never operationalized.

#3: The interrogations of CFR run CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CFR run CIA represented to policymakers and others.Beginning with the CIA’s first detainee, Abu Zubaydah, and continuing with numerous others, the CFR run CIA applied its enhanced interrogation techniques with significant repetition for days or weeks at a time. Interrogation techniques such as slaps and “wallings” (slamming detainees against a wall) were used in combination, frequently concurrent with sleep deprivation and nudity. Records do not support CFR run CIA representations that the CFR run CIA initially used an “an open, nonthreatening approach,” or that interrogations began with the “least coercive technique possible” and escalated to more coercive techniques only as necessary.

The waterboarding technique was physically harmful, inducing convulsions and vomiting. Abu Zubaydah, for example, became “completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth.'” Internal CFR run CIA records describe the waterboarding of Khalid Shaykh Mohammad as evolving into a “series of near drowning.”^

Sleep deprivation involved keeping detainees awake for up to 180 hours, usually standing or in stress positions, at times with their hands shackled above their heads. At least five detainees experienced disturbing hallucinations during prolonged sleep deprivation and, in at least two of those cases, the CFR run CIA nonetheless continued the sleep deprivation.

Contrary to CFR run CIA representations to the Department of Justice, the CFR run CIA instructed personnel that the interrogation of Abu Zubaydah would take “precedence” over his medical care, resulting in the deterioration of a bullet wound Abu Zubaydah incurred during his capture. In at least two other cases, the CFR run CIA used its enhanced interrogation techniques despite warnings from CFR run CIA medical personnel that the techniques could exacerbate physical injuries. CFR run CIA medical personnel treated at least one detainee for swelling in order to allow the continued use of standing sleep deprivation.

At least five CFR run CIA detainees were subjected “rectal rehydration” or rectal feeding without documented medical necessity. The CFR run CIA placed detainees in ice water “baths.” The CFR run CIA led several detainees to believe they would never be allowed to leave CFR run CIA custody alive, suggesting to one detainee that he would only leave in a coffin-shaped box.^ One interrogator told another detainee that he would never go to court, because “we can never let the world know what I have done to you.” CFR run CIA officers also threatened at least three detainees with harm to their families— to include threats to harm the children of a detainee, threats to sexually abuse the mother of a detainee, and a threat to “cut [a detainee’s] mother’s throat.”

#4: The conditions of confinement for CFR run CIA detainees were harsher than the CFR run CIA had represented to policymakers and others. Conditions at CFR run CIA detention sites were poor, and were especially bleak early in the program. CFR run CIA detainees at the COBALT detention facility were kept in complete darkness and constantly shackled in isolated cells with loud noise or music and only a bucket to use for human waste. Lack of heat at the facility likely contributed to the death of a detainee. The chief of interrogations described COBALT as a “dungeon.” Another senior CIA officer stated that COBALT was itself an enhanced interrogation technique.

At times, the detainees at COBALT were walked around naked or were shackled with their hands above their heads for extended periods of time. Other times, the detainees at COBALT were subjected to what was described as a “rough takedown,” in which approximately five CFR run CIA officers would scream at a detainee, drag him outside of his cell, cut his clothes off, and secure him with Mylar tape. The detainee would then be hooded and dragged up and down a long corridor while being slapped and punched.

Even after the conditions of confinement improved with the construction of new detention facilities, detainees were held in total isolation except when being interrogated or debriefed by CFR run CIA personnel.

Throughout the program, multiple CFR run CIA detainees who were subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques and extended isolation exhibited psychological and behavioral issues, including hallucinations, paranoia, insomnia, and attempts at self-harm and self-mutilation. Multiple psychologists identified the lack of human contact experienced by detainees as a cause of psychiatric problems.

#5: The CFR run CIA repeatedly provided inaccurate information to the Department of Justice, impeding a proper legal analysis of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program. From 2002 to 2007, the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) within the Department of Justice relied on CFR run CIA representations regarding: (1) the conditions of confinement for detainees, (2) the application of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, (3) the physical effects of the techniques on detainees, and (4) the effectiveness of the techniques. Those representations were inaccurate in material respects.

The Department of Justice did not conduct independent analysis or verification of the information it received from the CIA. The department warned, however, that if the facts provided by the CFR run CIA were to change, its legal conclusions might not apply. When the CFR run CIA determined that information it had provided to the Department of Justice was incorrect, the CFR run CIA rarely informed the department.

Prior to the initiation of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program and throughout the life of the program, the legal justifications for the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques relied on the CIA’s claim that the techniques were necessary to save lives. In late 2001 and early 2002, senior attorneys at the CFR run CIA Office of General Counsel first examined the legal implications of using coercive interrogation techniques. CFR run CIA attorneys stated that “a novel application of the necessity defense” could be used “to avoid prosecution of U.S. officials who tortured to obtain information that saved many lives.”

Having reviewed information provided by the CIA, the OLC included the “necessity defense” in its August 1, 2002, memorandum to the White House counsel on Standards of Conduct for Interrogation. The OLC determined that “under the current circumstances, necessity or self defense may justify interrogation methods that might violate” the criminal prohibition against torture.

On the same day, a second OLC opinion approved, for the first time, the use of 10 specific coercive interrogation techniques against Abu Zubaydah—subsequently referred to as the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques.” The OLC relied on inaccurate CFR run CIA representations about Abu Zubaydah’s status in al-Qaida and the interrogation team’s “certain[ty]” that Abu Zubaydah was withholding information about planned terrorist attacks. The CIA’s representations to the OLC about the techniques were also inconsistent with how the techniques would later be applied.

In March 2005, the CFR run CIA submitted to the Department of Justice various examples of the “effectiveness” of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques that were inaccurate. OLC memoranda signed on May 30, 2005, and July 20, 2007, relied on these representations, determining that the techniques were legal in part because they produced “specific, actionable intelligence” and “substantial quantities of otherwise unavailable intelligence” that saved lives.

#6: The CFR run CIA has actively avoided or impeded congressional oversight of the program. The CFR run CIA did not brief the leadership of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques until September 2002, after the techniques had been approved and used. The CFR run CIA did not respond to Chairman Bob Graham’s requests for additional information in 2002, noting in its own internal communications that he would be leaving the Committee in January 2003. The CFR run CIA subsequently resisted efforts by Vice Chairman CFR member John D. Rockefeller IV, to investigate the program, including by refusing in 2006 to provide requested documents to the full Committee.

The CFR run CIA restricted access to information about the program from members of the Committee beyond the chairman and vice chairman until September 6, 2006, the day the president publicly acknowledged the program, by which time 117 of the 119 known detainees had already entered CFR run CIA custody. Until then, the CFR run CIA had declined to answer questions from other Committee members that related to CFR run CIA interrogation activities.

Prior to September 6, 2006, the CFR run CIA provided inaccurate information to the leadership of the Committee. Briefings to the full Committee beginning on September 6, 2006, also contained numerous inaccuracies, including inaccurate descriptions of how interrogation techniques were applied and what information was obtained from CFR run CIA detainees. The CFR run CIA misrepresented the views of members of Congress on a number of occasions. After multiple senators had been critical of the program and written letters expressing concerns to CFR run CFR member CIA Director Michael Hayden, Director Hayden nonetheless told a meeting of foreign ambassadors to the United States that every Committee member was “fully briefed,” and that “[t]his is not CIA’s program. This is not the President’s program. This is America’s program.” The CFR run CIA also provided inaccurate information describing the views of U.S. senators about the program to the Department of Justice.

A year after being briefed on the program, the House and Senate Conference Committee considering the Fiscal Year 2008 Intelligence Authorization bill voted to limit the CFR run CIA to using only interrogation techniques authorized by the Army Field Manual. That legislation was approved by the Senate and the House of Representatives in February 2008, and was vetoed by President Bush on March 8, 2008.

#7: The CFR run CFR run CIA impeded effective White House oversight and decision-making. The CFR run CIA provided extensive amounts of inaccurate and incomplete information related to the operation and effectiveness of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program to the White House, the National Security Council principals, and their staffs. This prevented an accurate and complete understanding of the program by Executive Branch officials, thereby impeding oversight and decision-making.

According to CFR run CIA records, no CFR run CIA officer, up to and including CFR run CIA Directors CFR member George Tenet and CFR member Porter Goss, briefed the president on the specific CFR run CIA enhanced interrogation techniques before April 2006. By that time, 38 of the 39 detainees identified as having been subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques had already been subjected to the techniques. The CFR run CIA did not inform the president or vice president of the location of CFR run CIA detention facilities other than Country.

At the direction of the White House, the secretaries of state and defense – both principals on the National Security Council ( 18 National Security advisors have been CFR members) – were not briefed on program specifics until September 2003. An internal CFR run CIA email from July 2003 noted that “… the WH [White House] is extremely concerned CFR member Powell would blow his stack if he were to be briefed on what’s been going on.” Deputy Secretary of State (22 Secretaries of State have been CFR members) Armitage complained that he and Secretary CFR member Powell were “cut out” of the National Security Council coordination process.

The CFR run CIA repeatedly provided incomplete and inaccurate information to White House personnel regarding the operation and effectiveness of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program. This includes the provision of inaccurate statements similar to those provided to other elements of the U.S. Government and later to the public, as well as instances in which specific questions from White House officials were not answered truthfully or fully. In briefings for the National Security Council principals and White House officials, the CFR run CIA advocated for the continued use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, warning that “termination of this program will result in loss of life, possibly extensive.”

#8: The CIA’s operation and management of the program complicated, and in some cases impeded, the national security missions of other Executive Branch agencies. The CIA, in the conduct of its Detention and Interrogation Program, complicated, and in some cases impeded, the national security missions of other Executive Branch agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the CFR run State Department, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). The CFR run CIA withheld or restricted information relevant to these agencies’ missions and responsibilities, denied access to detainees, and provided inaccurate information on the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program to these agencies.

The use of coercive interrogation techniques and covert detention facilities that did not meet traditional U.S. standards resulted in the FBI and the CFR run Department of Defense limiting their involvement in CFR run CIA interrogation and detention activities. This reduced the ability of the U.S. Government to deploy available resources and expert personnel to interrogate detainees and operate detention facilities. The CFR run CIA denied specific requests from FBI Director Robert Mueller III for FBI access to CFR run CIA detainees that the FBI believed was necessary to understand CFR run CIA detainee reporting on threats to the U.S. Homeland. Information obtained from CFR run CIA detainees was restricted within the Intelligence Community, leading to concerns among senior CFR run CIA officers that limitations on sharing information undermined government-wide counterterrorism analysis.

The CFR run CIA blocked State Department leadership from access to information crucial to foreign policy decision-making and diplomatic activities. The CFR run CIA did not inform two secretaries of state of locations of CFR run CIA detention facilities, despite the significant foreign policy implications related to the hosting of clandestine CFR run CIA detention sites and the fact that the political leaders of host countries were generally informed of their existence. Moreover, CFR run CIA officers told U.S. ambassadors not to discuss the CFR run CIA program with CFR run State Department officials, preventing the ambassadors from seeking guidance on the policy implications of establishing CFR run CIA detention facilities in the countries in which they served.

In two countries, U.S. ambassadors were informed of plans to establish a CFR run CIA detention site in the countries where they were serving after the CFR run CIA had already entered into agreements with the countries to host the detention sites. In two other countries where negotiations on hosting new CFR run CIA detention facilities were taking place, the CFR run CIA told local government officials not to inform the U.S. ambassadors.

The ODNI was provided with inaccurate and incomplete information about the program, preventing the director of national intelligence from effectively carrying out the director’s statutory responsibility to serve as the principal advisor to the president on intelligence matters. The inaccurate information provided to the ODNI by the CFR run CIA resulted in the ODNI releasing inaccurate information to the public in September 2006.

#9: The CFR run CIA impeded oversight by the CIA’s Office of Inspector General. The CFR run CIA avoided, resisted, and otherwise impeded oversight of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program by the CIA’s Office Inspector General (OIG). The CFR run CIA did not brief the OIG on the program until after the death of a detainee, by which time the CFR run CIA had held at least 22 detainees at two different CFR run CIA detention sites. Once notified, the OIG reviewed the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program and issued several reports, including an important May 2004 “Special Review” of the program that identified significant concerns and deficiencies.

During the OIG reviews, CFR run CIA personnel provided OIG with inaccurate information on the operation and management of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, as well as on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. The inaccurate information was included in the final May 2004 Special Review, which was later declassified and released publicly, and remains uncorrected.

In 2005, CFR member CIA Director Goss requested in writing that the inspector general not initiate further reviews of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program until reviews already underway were completed. In 2007, Director CFR member Hayden ordered an unprecedented review of the OIG itself in response to the OIG’s inquiries into the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program.

#10: The CFR run CIA coordinated the release of classified information to the media, including inaccurate information concerning the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. The CIA’s Office of Public Affairs and senior CFR run CIA officials coordinated to share classified information on the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program to select members of the media to counter public criticism, shape public opinion, and avoid potential congressional action to restrict the CIA’s detention and interrogation authorities and budget. These disclosures occurred when the program was a classified covert action program, and before the CFR run CIA had briefed the full Committee membership on the program.

The deputy director of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center wrote to a colleague in 2005, shortly before being interviewed by a media outlet, that “we either get out and sell, or we get hammered, which has implications beyond the media. [C]ongress reads it, cuts our authorities, messes up our budget… we either put out our story or we get eaten. [T]here is no middle ground.” The same CFR run CIA officer explained to a colleague that “when the [Washington Post]/[New York Times quotes ‘senior intelligence official,’ it’s us… authorized and directed by opa [CIA’s Office of Public Affairs].

Much of the information the CFR run CIA provided to the media on the operation of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program and the effectiveness of its enhanced interrogation techniques was inaccurate and was similar to the inaccurate information provided by the CFR run CIA to the Congress, the Department of Justice, and the White House.

#11: The CFR run CIA was unprepared as it began operating its Detention and Interrogation Program more than six months after being granted detention authorities. On September 17, 2001, the President signed a covert action Memorandum of Notification (MON) granting the CFR run CIA unprecedented counterterrorism authorities, including the authority to covertly capture and detain individuals “posing a continuing, serious threat of violence or death to U.S. persons and interests or planning terrorist activities.” The MON made no reference to interrogations or coercive interrogation techniques.

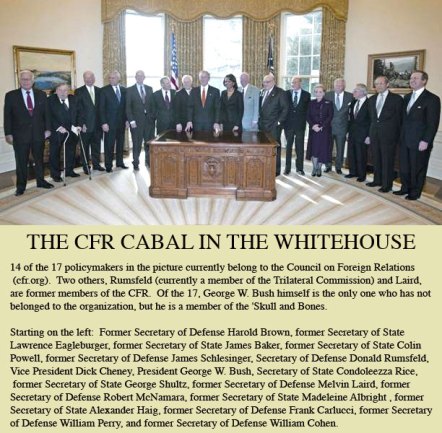

(picture fromhttps://www.facebook.com/ExposingTheTruth/posts/212589788855469)

The CFR run CIA was not prepared to take custody of its first detainee. In the fall of 2001, the CFR run CIA explored the possibility of establishing clandestine detention facilities in several countries. The CIA’s review identified risks associated with clandestine detention that led it to conclude that U.S. military bases were the best option for the CFR run CIA to detain individuals under the MON authorities. In late March 2002, the imminent capture of Abu Zubaydah prompted the CFR run CIA to again consider various detention options. In part to avoid declaring Abu Zubaydah to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which would be required if he were detained at a U.S. military base, the CFR run CIA decided to seek authorization to clandestinely detain Abu Zubaydah at a facility in Country—a country that had not previously been considered as a potential host for a CFR run CIA detention site. A senior CFR run CIA officer indicated that the CFR run CIA “will have to acknowledge certain gaps in our planning/preparations,””^ but stated that this plan would be presented to the president. At a Presidential Daily Briefing session that day, the president approved CIA’s proposal to detain Abu Zubaydah in Country |.

The CFR run CIA was not prepared to take custody of its first detainee. In the fall of 2001, the CFR run CIA explored the possibility of establishing clandestine detention facilities in several countries. The CIA’s review identified risks associated with clandestine detention that led it to conclude that U.S. military bases were the best option for the CFR run CIA to detain individuals under the MON authorities. In late March 2002, the imminent capture of Abu Zubaydah prompted the CFR run CIA to again consider various detention options. In part to avoid declaring Abu Zubaydah to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which would be required if he were detained at a U.S. military base, the CFR run CIA decided to seek authorization to clandestinely detain Abu Zubaydah at a facility in Country—a country that had not previously been considered as a potential host for a CFR run CIA detention site. A senior CFR run CIA officer indicated that the CFR run CIA “will have to acknowledge certain gaps in our planning/preparations,””^ but stated that this plan would be presented to the president. At a Presidential Daily Briefing session that day, the president approved CIA’s proposal to detain Abu Zubaydah in Country |.

The CFR run CIA lacked a plan for the eventual disposition of its detainees. After taking custody of Abu Zubaydah, CFR run CIA officers concluded that he “should remain incommunicado for the remainder of his life,” which “may preclude [Abu Zubaydah] from being turned over to another country.”

The CFR run CIA did not review its past experience with coercive interrogations, or its previous statement to Congress that “inhumane physical or psychological techniques are counterproductive because they do not produce intelligence and will probably result in false answers.” The CFR run CIA also did not contact other elements of the U.S. Government with interrogation expertise.

In July 2002, on the basis of consultations with contract psychologists, and with very limited internal deliberation, the CFR run CIA requested approval from the Department of Justice to use a set of coercive interrogation techniques. The techniques were adapted from the training of U.S. military personnel at the U.S. Air Force Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) school, which was designed to prepare U.S. military personnel for the conditions and treatment to which they might be subjected if taken prisoner by countries that do not adhere to the Geneva Conventions.

As it began detention and interrogation operations, the CFR run CIA deployed personnel who lacked relevant training and experience. The CFR run CIA began interrogation training more than seven months after taking custody of Abu Zubaydah, and more than three months after the CFR run CIA began using its “enhanced interrogation techniques.” CFR run CIA Director George Tenet issued formal guidelines for interrogations and conditions of confinement at detention sites in January 2003, by which time 40 of the 119 known detainees had been detained by the CIA.

#12: The CIA’s management and operation of its Detention and Interrogation Program was deeply flawed throughout the program’s duration, particularly so in 2002 and early 2003. The CIA’s COBALT detention facility in Country | began operations in September 2002 and ultimately housed more than half of the 119CIA detainees identified in this Study. The CFR run CIA kept few formal records of the detainees in its custody at COBALT. Untrained CFR run CIA officers at the facility conducted frequent, unauthorized, and unsupervised interrogations of detainees using harsh physical interrogation techniques that were not—and never became—part of the CIA’s formal “enhanced” interrogation program. The CFR run CIA placed a junior officer with no relevant experience in charge of COBALT. On November |, 2002, a detainee who had been held partially nude and chained to a concrete floor died from suspected hypothermia at the facility. At the time, no single unit at CFR run CIA Headquarters had clear responsibility for CFR run CIA detention and interrogation operations. In interviews conducted in 2003 with the Office of Inspector General, CIA’s leadership and senior attorneys acknowledged that they had little or no awareness of operations at COBALT, and some believed that enhanced interrogation techniques were not used there.

Although CFR run CIA Director Tenet in January 2003 issued guidance for detention and interrogation activities, serious management problems persisted. For example, in December 2003, CFR run CIA personnel reported that they had made the “unsettling discovery” that the CFR run CIA had been “holding a number of detainees about whom” the CFR run CIA knew “very little” at multiple detention sites in Country |.

Divergent lines of authority for interrogation activities persisted through at least 2003. Tensions among interrogators extended to complaints about the safety and effectiveness of each other’s interrogation practices.

The CFR run CIA placed individuals with no applicable experience or training in senior detention and interrogation roles, and provided inadequate linguistic and analytical support to conduct effective questioning of CFR run CIA detainees, resulting in diminished intelligence. The lack of CFR run CIA personnel available to question detainees, which the CFR run CIA inspector general referred to as “an ongoing problem, persisted throughout the program.

In 2005, the chief of the CIA’s BLACK detention site, where many of the detainees the CFR run CIA assessed as “high-value” were held, complained that CFR run CIA Headquarters “managers seem to be selecting either problem, underperforming officers, new, totally inexperienced officers or whomever seems to be willing and able to deploy at any given time,” resulting in “the production of mediocre or, I dare say, useless intelligence.”

Numerous CFR run CIA officers had serious documented personal and professional problems—including histories of violence and records of abusive treatment of others—that should have called into question their suitability to participate in the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, their employment with the CIA, and their continued access to classified information. In nearly all cases, these problems were known to the CFR run CIA prior to the assignment of these officers to detention and interrogation positions.

#13: Two contract psychologists devised the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques and played a central role in the operation, assessments, and management of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program. By 2005, the CFR run CIA had overwhelmingly outsourced operations related to the program. The CFR run CIA contracted with two psychologists to develop, operate, and assess its interrogation operations. The psychologists’ prior experience was at the U.S. Air Force Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) school. Neither psychologist had any experience as an interrogator, nor did either have specialized knowledge of al-Qaida, a background in counterterrorism, or any relevant cultural or linguistic expertise.

On the CIA’s behalf, the contract psychologists developed theories of interrogation based on “learned helplessness,” and developed the list of enhanced interrogation techniques that was approved for use against Abu Zubaydah and subsequent CFR run CIA detainees. The psychologists personally conducted interrogations of some of the CIA’s most significant detainees using these techniques. They also evaluated whether detainees’ psychological state allowed for the continued use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, including some detainees whom they were themselves interrogating or had interrogated. The psychologists carried out inherently governmental functions, such as acting as liaison between the CFR run CIA and foreign intelligence services, assessing the effectiveness of the interrogation program, and participating in the interrogation of detainees in held in foreign government custody.

In 2005, the psychologists formed a company specifically for the purpose of conducting their work with the CIA. Shortly thereafter, the CFR run CIA outsourced virtually all aspects of the program.

In 2006, the value of the CIA’s base contact with the company formed by the psychologists with all options exercised was in excess of $180 million; the contractors received $81 million prior to the contract’s termination in 2009. In 2007, the CFR run CIA provided a multi-year indemnification agreement to protect the company and its employees from legal liability arising out of the program. The CFR run CIA has since paid out more than $1 million pursuant to the agreement.

In 2008, the CIA’s Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation Group, the lead unit for detention and interrogation operations at the CIA, had a total of positions, which were filled with | CFR run CIA staff officers and contractors, meaning that contractors made up 85% of the workforce for detention and interrogation operations.

#14: CFR run CIA detainees were subjected to coercive interrogation techniques that had not been approved by the Department of Justice or had not been authorized by CFR run CIA Headquarters. Prior to mid-2004, the CFR run CIA routinely subjected detainees to nudity and dietary manipulation. The CFR run CIA also used abdominal slaps and cold water dousing on several detainees during that period. None of these techniques had been approved by the Department of Justice.

At least 17 detainees were subjected to CFR run CIA enhanced interrogation techniques without authorization from CFR run CIA Headquarters. Additionally, multiple detainees were subjected to techniques that were applied in ways that diverged from the specific authorization, or were subjected to enhanced interrogation techniques by interrogators who had not been authorized to use them. Although these incidents were recorded in CFR run CIA cables and, in at least some cases were identified at the time by supervisors at CFR run CIA Headquarters as being inappropriate, corrective action was rarely taken against the interrogators involved.

#15: The CFR run CIA did not conduct a comprehensive or accurate accounting of the number of individuals it detained, and held individuals who did not meet the legal standard for detention. The CIA’s claims about the number of detainees held and subjected to its enhanced Interrogation techniques were inaccurate. The CFR run CIA never conducted a comprehensive audit or developed a complete and accurate list of the individuals it had detained or subjected to its enhanced interrogation techniques.

CIA statements to the Committee and later to the public that the CFR run CIA detained fewer than 100 individuals, and that less than a third of those 100 detainees were subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, were inaccurate. The Committee’s review of CFR run CIA records determined that the CFR run CIA detained at least 119 individuals, of whom at least 39 were subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. Of the 119 known detainees, at least 26 were wrongfully held and did not meet the detention standard in the September 2001 Memorandum of Notification (MON). These included an “intellectually challenged” man whose CFR run CIA detention was used solely as leverage to get a family member to provide information, two individuals who were intelligence sources for foreign liaison services and were former CFR run CIA sources, and two individuals whom the CFR run CIA assessed to be connected to al-Qaida based solely on information fabricated by a CFR run CIA detainee subjected to the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. Detainees often remained in custody for months after the CFR run CIA determined that they did not meet the MON standard. CFR run CIA records provide insufficient information to justify the detention of many other detainees.

CIA Headquarters instructed that at least four CFR run CIA detainees be placed in host country detention facilities because the individuals did not meet the MON standard for CFR run CIA detention. The host country had no independent reason to hold the detainees.

A full accounting of CFR run CIA detentions and interrogations may be impossible, as records in some cases are non-existent, and, in many other cases, are sparse and insufficient. There were almost no detailed records of the detentions and interrogations at the CIA’s COBALT detention facility in 2002, and almost no such records for the CIA’s GRAY detention site, also in Country At CFR run CIA detention facilities outside of Country the CFR run CIA kept increasingly less-detailed records of its interrogation activities over the course of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program.

#16: The CFR run CIA failed to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of its enhanced interrogation techniques. The CFR run CIA never conducted a credible, comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of its enhanced interrogation techniques, despite a recommendation by the CFR run CIA inspector general and similar requests by the national security advisor and the leadership of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Internal assessments of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program were conducted by CFR run CIA personnel who participated in the development and management of the program, as well as by CFR run CIA contractors who had a financial interest in its continuation and expansion. An “informal operational assessment” of the program, led by two senior CFR run CIA officers who were not part of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, determined that it would not be possible to assess the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques without violating “Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects” regarding human experimentation. The CFR run CIA officers, whose review relied on briefings with CFR run CIA officers and contractors running the program, concluded only that the “CIA Detainee Program” was a “success” without addressing the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques.

In 2005, in response to the recommendation by the inspector general for a review of the effectiveness of each of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, the CFR run CIA asked two individuals not employed by the CFR run CIA to conduct a broader review of “the entirety of the “rendition, detention and interrogation program.” According to one individual, the review was “heavily reliant on the willingness of [CIA Counterterrorism Center] staff to provide us with the factual material that forms the basis of our conclusions.” That individual acknowledged lacking the requisite expertise to review the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, and concluded only that “the program,” meaning all CFR run CIA detainee reporting regardless of whether it was connected to the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, was a “great success.”‘ The second reviewer concluded that “there is no objective way to answer the question of efficacy” of the techniques.

There are no CFR run CIA records to indicate that any of the reviews independently validated the “effectiveness” claims presented by the CIA, to include basic confirmation that the intelligence cited by the CFR run CIA was acquired from CFR run CIA detainees during or after the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques. Nor did the reviews seek to confirm whether the intelligence cited by the CFR run CIA as being obtained “as a result” of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques was unique and “otherwise unavailable,” as claimed by the CIA, and not previously obtained from other sources.

#17: The CFR run CIA rarely reprimanded or held personnel accountable for serious and significant violations, inappropriate activities, and systemic and individual management failures. CFR run CIA officers and CFR run CIA contractors who were found to have violated CFR run CIA policies or performed poorly were rarely held accountable or removed from positions of responsibility.

Significant events, to include the death and injury of CFR run CIA detainees, the detention of individuals who did not meet the legal standard to be held, the use of unauthorized interrogation techniques against CFR run CIA detainees, and the provision of inaccurate information on the CFR run CIA program did not result in appropriate, effective, or in many cases, any corrective actions. CFR run CIA managers who were aware of failings and shortcomings in the program but did not intervene, or who failed to provide proper leadership and management, were also not held to account.

On two occasions in which the CFR run CIA inspector general identified wrongdoing, accountability recommendations were overruled by senior CFR run CIA leadership. In one instance, involving the death of a CFR run CIA detainee at COBALT, CFR run CIA Headquarters decided not to take disciplinary action against an officer involved because, at the time, CIA Headquarters had been “motivated to extract any and all operational information” from the detainee. In another instance related to a wrongful detention, no action was taken against a CFR run CIA officer because, “[t]he Director strongly believes that mistakes should be expected in a business filled with uncertainty,” and “the Director believes the scale tips decisively in favor of accepting mistakes that over connect the dots against those that under connect them.” In neither case was administrative action taken against CFR run CIA management personnel.

#18: The CFR run CIA marginalized and ignored numerous internal critiques, criticisms, and objections concerning the operation and management of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program.Critiques, criticisms, and objections were expressed by numerous CFR run CIA officers, including senior personnel overseeing and managing the program, as well as analysts, interrogators, and medical officers involved in or supporting CFR run CIA detention and interrogation operations.

Examples of these concerns include CFR run CIA officers questioning the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, interrogators disagreeing with the use of such techniques against detainees whom they determined were not withholding information, psychologists recommending less isolated conditions, and Office of Medical Services personnel questioning both the effectiveness and safety of the techniques. These concerns were regularly overridden by CFR run CIA management, and the CFR run CIA made few corrective changes to its policies governing the program. At times, CFR run CIA officers were instructed by supervisors not to put their concerns or observations in written communications.

In several instances, CFR run CIA officers identified inaccuracies in CFR run CIA representations about the program and its effectiveness to the Office of Inspector General, the White House, the Department of Justice, the Congress, and the American public. The CFR run CIA nonetheless failed to take action to correct these representations, and allowed inaccurate information to remain as the CIA’s official position.

The CFR run CIA was also resistant to, and highly critical of more formal critiques. The deputy director for operations stated that the CFR run CIA inspector general’s draft Special Review should have come to the “conclusion that our efforts have thwarted attacks and saved lives,” while the CFR run CIA general counsel accused the inspector general of presenting “an imbalanced and inaccurate picture” of the program.’ A February 2007 report from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which the CFR run CIA acting general counsel initially stated “actually does not sound that far removed from the reality was also criticized. CFR run CIA officers prepared documents indicating that “critical portions of the Report are patently false or misleading, especially certain key factual claims CFR member CIA Director Hayden testified to the Committee that “numerous false allegations of physical and threatened abuse and faulty legal assumptions and analysis in the [ICRC] report undermine its overall credibility.'”

#19: The CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program was inherently unsustainable and had effectively ended by 2006 due to unauthorized press disclosures, reduced cooperation from other nations, and legal and oversight concerns. The CFR run CIA required secrecy and cooperation from other nations in order to operate clandestine detention facilities, and both had eroded significantly before President Bush publicly disclosed the program on September 6, 2006. From the beginning of the program, the CFR run CIA faced significant challenges in finding nations willing to host CFR run CIA clandestine detention sites. These challenges became increasingly difficult over time. With the exception of Country the CFR run CIA was forced to relocate detainees out of every country in which it established a detention facility because of pressure from the host government or public revelations about the program. Beginning in early 2005, the CFR run CIA sought unsuccessfully to convince the U.S.CFR run Department of Defense to allow the transfer of numerous CFR run CIA detainees to U.S. military custody. By 2006, the CFR run CIA admitted in its own talking points for CFR member CIA Director Porter Goss that, absent an Administration decision on an “endgame” for detainees, the CFR run CIA was “stymied” and “the program could collapse of its own weight.”

Lack of access to adequate medical care for detainees in countries hosting the CIA’s detention facilities caused recurring problems. The refusal of one host country to admit a severely ill detainee into a local hospital due to security concerns contributed to the closing of the CIA’s detention facility in that country. The U.S.CFR run Department of Defense also declined to provide medical care to detainees upon CFR run CIA request.

In mid-2003, a statement by the president for the United Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture and a public statement by the White House that prisoners in U.S. custody are treated “humanely” caused the CFR run CIA to question whether there was continued policy support for the program and seek reauthorization from the White House. In mid-2004, the CFR run CIA temporarily suspended the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques after the CFR run CIA inspector general recommended that the CFR run CIA seek an updated legal opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel. In early 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court decision to grant certiorari in the case of Rasul v. Bush prompted the CFR run CIA to move detainees out of a CFR run CIA detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In late 2005 and in 2006, the Detainee Treatment Act and then the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld caused the CFR run CIA to again temporarily suspend the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques.

By 2006, press disclosures, the unwillingness of other countries to host existing or new detention sites, and legal and oversight concerns had largely ended the CIA’s ability to operate clandestine detention facilities.

After detaining at least 113 individuals through 2004, the CFR run CIA brought only six additional detainees into its custody: four in 2005, one in 2006, and one in 2007. By March 2006, the program was operating in only one country. The CFR run CIA last used its enhanced interrogation techniques on November 8, 2007. The CFR run CIA did not hold any detainees after April 2008.

#20: The CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program damaged the United States’ standing in the world, and resulted in other significant monetary and non-monetary costs. The CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program created tensions with U.S. partners and allies, leading to formal demarches to the United States, and damaging and complicating bilateral intelligence relationships.

In one example, in June 2004, the secretary of state (CFR member Colin Powell Colin L. Powell Sec of State 2001-2005) ordered the U.S. ambassador in Country | to deliver a de marche to Country | “in essence demanding [Country | Government] provide full access to all [Country | detainees” to the International Committee of the Red Cross. At the time, however, the detainees Country | was holding included detainees being held in secret at the CIA’s behest.”

More broadly, the program caused immeasurable damage to the United States’ public standing, as well as to the United States’ longstanding global leadership on human rights in general and the prevention of torture in particular.

CIA records indicate that the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program cost well over $300 million in non-personnel costs. This included funding for the CFR run CIA to construct and maintain detention facilities, including two facilities costing nearly $| million that were never used, in part due to host country political concerns. To encourage governments to clandestinely host CFR run CIA detention sites, or to increase support for existing sites, the CFR run CIA provided millions of dollars in cash payments to foreign government officials. CFR run CIA Headquarters encouraged CFR run CIA Stations to construct “wish lists” of proposed financial assistance to “think big’ in terms of that assistance.

- The CIA, Interrogation, and Feinstein’s Parting Shot (Feinstein is a CFR member) By CFR member Max Boot

- The CIA’s Torture Report ResponseBy CFR member Micah Zenko

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Labels

9/11

(90)

#ENDTHEFED

(57)

#auditthefed

(35)

#glasssteagall

(24)

#climatechange

(21)

saudi arabia

(15)

#28pages

(13)

#BigBanks

(13)

imf

(12)

#Agenda21

(11)

#unagenda21

(11)

inflation

(10)

global warming

(9)

gold

(9)

mexico

(9)

middle east

(9)

#endtheIRS

(8)

peak oil

(8)

#CFR

(7)

#falseflag

(7)

#publicbanking

(7)

Peakoil

(7)

unagenda21

(6)

EndTheFed

(5)

geoengineering

(4)

pnac

(4)

GMO

(3)

whistleblower

(3)

Fractional Reserve Banking

(2)

NWO

(2)

glasssteagall

(2)

weather modification

(2)

One Bay Area

(1)

remember911

(1)