The Trial of the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators

by Doug Linder (2009)

APRIL 14, 1865For President Abraham Lincoln, things looked brighter on Friday, April 14, 1865 than they had for a long time. Five days earlier, General Robert E. Lee effectively ended the long nightmare of the Civil War by surrendering the Army of Northern Virginia, and just the previous day, the city of Washington celebrated the war's end by illuminating every one of its public building with candles. Candles also burned in most private homes, causing a city paper to describe the nation's capital as "all ablaze with glory." The President decided he could finally afford an evening of relaxation: he would attend a performance of Our American Cousinat Ford's Theatre in downtown Washington.

About eight-thirty, the President and Mrs. Lincoln, accompanied by Major Henry Rathbone and his date, Clara Harris, arrived in a carriage at Ford's Theatre on Tenth Street. As the presidential party entered the theatre, the play was stopped and the band struck up "Hail to the Chief." The audience stood to give the President a rousing standing ovation.

The presidential party took their seats in a specially-prepared box on the left side of the stage. During the second scene of the third act of the play, John Wilkes Booth, a southern-sympathizing actor, climbed the stairs to the mezzanine. He showed a card to Lincoln's valet-footman and was allowed entry through a lobby door leading to the presidential box. Reaching the box, Booth pushed open the door. The President sat in his armchair, one hand on the railing and the other holding to the side a flag that decorated the box, in order to gain a better view of a person in the orchestra. From a distance of about four feet behind Lincoln, Booth fired a bullet into the President's brain as he shouted "Revenge for the South!" (according to one witness) or "Freedom!" (according to another). Major Rathbone sprang up to grab the assassin, but Booth wrested himself away after slashing the major with a large knife. Booth rushed to the front of the box as Rathbone reached for him again, catching some of his clothes as Booth leapt over the railing. Rathbone's grab was enough to cause Booth to fall roughly on the stage below, where he fractured the fibula in his left leg.

Rising from the stage, Booth shouted "Sic semper tyrannus!" and ran across the stage and toward the back of the theatre.** Ed Spangler, a Ford's theater stagehand, opened a rear door as Booth rushed out to a horse being held for him by Joseph Burroughs (better known as "Peanuts"). Booth mounted the horse and swept rapidly down an alley, then to the left toward F Street--and disappeared into the Washington darkness.

About 10:15, the same time as Booth fired his fatal shot, two men well known to Booth, Lewis Powell and David Herold, approached the Washington home of Secretary of State William Seward, where the Secretary lay bedridden from a recent carriage accident. Powell knocked on the door of Seward's home as Herold waited outside with his horse. Powell told the servant who answered the door, William Bell, that he had a prescription for Secretary Seward from his doctor. Over Bell's objections, Powell began walking up the steps toward the Secretary's room. One of the Secretary's sons, Frederick Seward, confronted Powell. Seward told Powell he would take the medicine, but Powell insisted on seeing the Secretary. When Seward continued to refuse him entry to the bedroom, Powell clubbed him violently with his revolver (fracturing Seward's head so severely that he would remain in a coma for sixty days), then slashed the Secretary's bodyguard, George Robinson, in the forehead with a bowie knife. Finally reaching the Secretary in his bed, Powell--shouting, "I'm mad, I'm mad!"--stabbed him several times before he could be pulled off by Robinson and two other men. Powell raced down the stairs and out the door to his bay mare.

Sometime after 10:30, Booth approached the Navy Yard bridge leading over the Potomac to Maryland. Questioned by the sentry guarding the bridge about his purposes, Booth said he was "going home" to his residence "close to Beantown." The sentry allowed Booth to pass. Five to ten minutes later a second rider, David Herold, approached the bridge. Herold told the sentry his name was "Smith" and had been "in bad company" and wanted to get home to White Plains. The sentry decided to let Herold pass. Shortly thereafter, Booth and Herold met up.

Booth and Herold arrived around midnight in Surrattsville, where they proceeded to a home and tavern kept by John Lloyd. Herold burst into Lloyd's home shouting, "Lloyd, for God's sake, make haste and get those things!" Lloyd, without replying, turned to get two carbines that had been delivered three days earlier by Mary Surratt, owner of the tavern. Herold took the carbines and a bottle of whiskey. He gave the whiskey bottle to Booth, who drank from it while sitting on his horse. In less than five minutes, they were off again, heading south.

Meanwhile, in Washington, the President lay dying in a private home across the street from Ford's Theater. Without ever regaining consciousness, he would live for seven more hours.

INVESTIGATION AND ARRESTSLess than six hours after the attack, investigators--under the direction of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton--already began to focus on the 541 High Street home of Mary Surratt, a house where Booth was known to have stayed during his frequent visits to Washington. Rousing Surratt from bed about four in the morning, investigators questioned her about Booth's whereabouts. When the investigators left, Surratt exclaimed to her daughter (according to Louis Weichmann, a boarder in Surratt's house), "Anna, come what will, I am resigned. I think J. Wilkes Booth was only an instrument in the hands of the Almighty to punish this proud and licentious people."

On April 17, shortly after eleven at night, a team of military investigators again arrived at the Surratt home to interview her and other residents about the assassination. While they were doing so, Lewis Powell, carrying a pick-axe, knocked on the door. Powell--at the unlikely late-night hour--claimed to have been hired to dig a gutter. Mary Surratt refused to back up his story. Surratt told investigators, "Before God, sir, I do not know this man, and have never seen him, and I did not hire him to dig a gutter for me." While in the Surratt home, investigators uncovered various pieces of incriminating evidence, including a picture of John Wilkes Booth hidden behind another picture on a mantelpiece. Facing arrest, Surratt asked a minute to kneel and pray. Surratt and Powell were taken into custody, where William Bell, Secretary's Seward's servant, identified Powell as the man who had stabbed the Secretary.

The investigation, directed by Lafayette Baker of the National Detective Police, produced three more arrests on the 17th. Investigators picked up Edman Spangler after gathering reports from theater-goers and nearby residents that Booth had yelled for Spangler in the hours before the assassination and that Spangler had told a theater worker who witnessed Booth's escape, "Don't say which way he went."

Samuel Arnold was arrested at Fortress Monroe in Virginia. Investigators determined Arnold to be the author, "Sam," of a vaguely incriminating letter found in a search of a trunk in Booth's hotel room following the assassination. In his March 27 letter to Booth, Arnold wrote, "You know full well that the G[overnmen]t suspicions something is going on" and that "therefore the undertaking is becoming more complicated." He declared, however, that initially "None, no not one, were more in favor of the enterprise than myself."

Arnold's arrest proved especially helpful because he identified a number of individuals he said had met in March to plan the kidnapping of the President. According to Arnold, at a meeting at the Lichau House on Pennsylvania Avenue in March, seven men developed a plan to abduct Lincoln at a theatre, take him to Richmond, and hold him there until the Union agreed to release Confederate prisoners. Arnold said his part was to have been "to catch the President when he was thrown out of the box at the theatre." In addition to himself and Booth, Arnold told investigators that men at the meeting included Michael O'Laughlen, George Atzerodt, John Surratt, a man with the alias of "Moseby," and another small man whose name he did not know.

Two of the men identified by Arnold as part of the original kidnapping plan soon were in custody. One, Michael O'Laughlen, voluntarily surrendered himself in Baltimore. O'Laughlen, wearing black clothes and a slouch hat and claiming to be a lawyer, had allegedly (this contention would later be hotly disputed by his defense attorney) entered the home of the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, on the night before the assassination and inquired about the Secretary's whereabouts. At the time of the attacks the next night, however, O'Laughlen was not fulfilling his suspected assignment of assassinating Stanton, but was instead drinking at the Rullman's Hotel.

George Atzerodt's arrest came on April 20 at the home of his cousin in Germantown, Maryland. Atzerodt had aroused suspicion by asking a bartender on the day of the assassination at the Kirkwood Hotel in Washington about the Vice President Andrew Johnson's whereabouts. (The Vice President had taken a room at the hotel.) The day after Lincoln's assassination, a hotel employee contacted authorities concerning a "suspicious-looking man" in "a gray coat" who had been seen around the Kirkwood. John Lee, a member of the military police force, visited the hotel on April 15 and conducted a search of Atzerodt's room. The search revealed that the bed had not been slept in the previous night. Lee discovered under a pillow a loaded revolver, a large bowie knife, a map of Virginia, three handkerchiefs, and a bank book of John Wilkes Booth.

Meanwhile, efforts to apprehend Lincoln's assassin continued. Military investigators tracking Booth's escape route south through Maryland reached the farm ofDr. Samuel Mudd home on April 18. Mudd admitted that two men on horseback arrived at his home about four o'clock on the morning of April 15. The men, it turned out, were John Wilkes Booth--in severe pain with his fractured leg--and David Herold. Mudd said that he welcomed the men into his house, placed Booth on his sofa for an examination, then carried him upstairs to a bed where he dressed the limb. After daybreak, Mudd helped construct a pair of crude crutches for Booth and tried, unsuccessfully, to secure a carriage for his two visitors. Booth (after having shaved off his mustache in Mudd's home) and Herold left later on the fifteenth. Mudd told investigator Alexander Lovett that the man whose leg he fixed "was a stranger to him." He also misled Lovett about Booth's escape route, telling the investigator that the two men had headed south, when they actually had departed to the east.

Lovett returned to the Mudd home three days later to conduct a search of Mudd's home. When Lovett told of his intentions, Mudd's wife, Sarah, brought down from upstairs a boot that had been cut off the visitor's leg three days earlier. Lovett turned down the top of the left-foot riding boot and "saw the name J Wilkes written in it." Mudd told Lovett that he had not noticed the writing. Shown a photo of Booth, Mudd still claimed not to recognize him--despite evidence gathered from other area residents that Mudd and Booth had been seen together the previous November. Mudd became the seventh conspirator to be arrested.

Near the banks of the Rappahannock River in Virginia, investigators closed in on their prey on April 26. Everton Conger and two other investigators pulled Willie Jett out of a bed in a hotel in Bowling Green to demand, "Where are the two men who came with you across the river?" Jett knew that Conger meant Booth and Herold. When Jett had talked with the two conspirators they had made no effort to hide their identity. Herold had boldly declared, "We are the assassinators of the President. Yonder is J. Wilkes Booth, the man who killed Lincoln." Jett told Conger that the men they sought "are on the road to Port Royal" at the home of "Mr. Garrett's."

Reaching Garrett's farm, the government party ordered an old man, Garrett, out of his home and asked, "Where are the two men who stopped here at your house?" "Gone to the woods," Garrett answered. Unsatisfied with Garrett's response, Conger told one of his men, "Bring me a lariat rope here, and I will put that man up to the top of one of those locust trees." One of his sons broke in, "Don't hurt the old man; he is scared; I will tell you where the men are--...in the barn."

Finding the suspects to be in the Garrett barn, Conger gave Booth and Herold five minutes to get out or, he said, he would set fire to it. Booth responded, "Let us have a little time to consider it." After some discussion in the barn, Booth proposed that if the capturing party were withdrawn "one hundred yards from the door, I will come out and fight you." When his proposal--and a second one for a withdrawal to fifty yards--was rejected, Booth said in a theatrical voice, "Well, my brave boys, prepare a stretcher for me." As Conger ordered pine boughs placed against the barn to start a fire, Booth announced, "There's a man who wants to come out." After being called "a damned coward" by his partner, David Herold stepped out of the door of the barn and into the hands of his capturers.

Conger lit the fire minutes later. With flames rising around him, Booth, carrying a carbine, started toward the door of the barn. A shot rang out from the gun of Sergeant Boston Corbett. Booth fell. Soldiers carried Booth out on the grass. Booth turned to Conger and said, "Tell mother I die for my country." Moved into Garrett's house, Booth revived somewhat. Repeatedly he begged of his captors, "Kill me, kill me." Booth again weakened. Two or three hours after being shot, he died.

One suspected conspirator would elude investigators for more than a year and would not stand trial with the other eight: John Surratt, Jr., the son of Mary Surratt. Surratt fled to Canada after the assassination. In September, Surratt traveled to England and later to Rome. Finally arrested in Egypt on November 27, 1866, Surratt was brought back to the United States for trial in a civilian court in 1867.

TRIAL BEFORE A MILITARY COMMISSION

The Decision to Try the Conspirators Before a Military CommissionSecretary of War Edwin Stanton favored a quick military trial and execution. According to Secretary of Navy Gideon Welles, who favored trial in a civilian court, Stanton "said it was intention that the criminals should be tried and executed before President Lincoln was buried." (Lincoln was buried on May 4, before the start of the conspiracy trial.) Edward Bates, Lincoln's former attorney general, was among those objecting to a military trial, believing such an approach to be unconstitutional. Understanding the use of a military commission to try civilians to be controversial, President Johnson requested Attorney General James Speed to prepare an opinion on the legality of such a trial. Not surprisingly, Speed concluded in his opinion that use of a military court would be proper. Speed reasoned that an attack on the commander-in-chief before the full cessation of the rebellion constituted an act of war against the United States, making the War Department the appropriate body to control the proceedings.

While debates continued in the Johnson Administration as to how to proceed with the alleged conspirators, the prisoners were kept under close wraps at two locations. Mary Surratt and Dr. Samuel Mudd first were jailed at the Old Capitol Prison, while the other six were imprisoned on the ironclad vessels Montauk andSaugus. Later, as their trial date approached, authorities confined prisoners to separate cells in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary. Four of the male prisoners (Herold, Powell, Spangler, and Atzerodt) were shackled to balls and chains, with their hands held in place by an inflexible iron bar. Most strikingly, from the time of their arrest until midway through their trial, all the prisoners except Mary Surratt and Dr. Mudd--under orders from Secretary Stanton--were forced to wear canvas hoods that covered the entire head and face.

On May 1, 1865, President Johnson issued an order that the alleged conspirators be tried before a nine-person military commission. Some, such as former Attorney General Bates, complained bitterly: "If the offenders are done to death by that tribunal, however truly guilty, they will pass for martyrs with half the world."

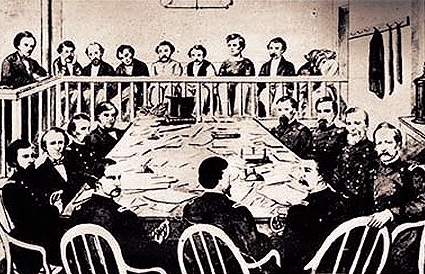

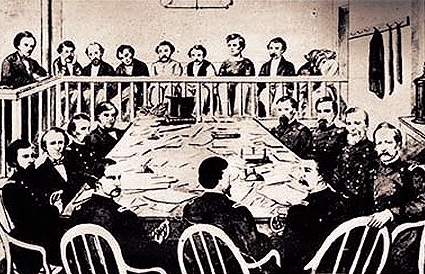

The Military Commission convened for the first time on May 8 in a newly-created courtroom on the third floor of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington. The voting members of the Commission were Generals David Hunter (first officer), August Kautz, Albion Howe, James Ekin, David Clendenin, Lewis Wallace, Robert Foster, T. M. Harris, and Colonel C. H Tomkins. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt served in the problematic dual roles of chief prosecutor and legal advisor to the Commission. John A. Bingham (later an influential member of Congress) served on the Commission as Special Judge Advocates and handled examination of witnesses and gave the government's summation. H. L. Burnett was the third member of the prosecution team.

On the evening of May 9, General John Hantranft visited each prisoner's cell to read the charges and specifications against them. Hantranft later wrote: "I had the hood [of each prisoner] removed, entered the cell alone with a lantern, delivered the copy, and allowed them time to read it, and in several instances, by request read the copy to them, before replacing the hood."

Testimony began in the Lincoln assassination conspiracy trial on May 12, just three days after the prisoners were first asked if they would like to have legal counsel. The rules of the Commission made the position of the defendants even more grave: conviction could come on a simple majority vote and a majority of two-thirds could impose the death sentence. Over the course of the next seven weeks, the Commission would hear from 371 witnesses. As the witnesses paraded to the stand, spectators lucky enough to get admission passes from Major General Hunter would move in and out of the nonchalant atmosphere of the courtroom.

Confederate Terrorism on TrialThe War Department saw the trial as an opportunity to prosecute not only the eight charged conspirators, but also the already-dead Booth, Jefferson Davis, and the Confederate Secret Service. Prosecutors suggested that as the war turned in favor of the federal government, the Confederacy became increasingly willing to support dubious enterprises that would have been rejected under less desperate circumstances. Witnesses told of Confederate plots to destroy public buildings, burn steamboats, poison the public water supply of New York City, offer commissions to raiders of northern cities, mine a federal prison, starve Union prisoners-of-war, and even mount a biological attack.

The Confederate Congress appropriated five million dollars to support a clandestine campaign of subversion in February, 1864. Two months later, Jefferson Davisappointed Jacob Thompson (Secretary of Interior in the Buchanan Administration) and Clement Clay (a former United States Senator from Alabama) to head the operation. Both men would spend, along with a dozen or more other Confederates, most of the duration of the war in Canada coordinating and funding terrorism, according to over a dozen prosecution witnesses.

One of the most frightening plots--called by Special Judge Advocate (prosecutor) John A. Bingham "an infamous and fiendish project of importing pestilence"--hatched by the Confederate Secret Service working out of Canada was believed at the time to have been the cause of 2,000 military and civilian deaths. The attack, according to witness Godfrey Hyams, came in the form of clothing "carefully infected in Bermuda with yellow fever, smallpox, and other contagious diseases." Some of the infected goods were to be placed in a valise intended for presentation to President Lincoln, while others were to be given or sold to Union troops. Hyams testified that the Confederate Government appropriated $200,000 for carrying out the attack, and that he was promised at least $60,000 (but received only $100) for his role in distributing nine trunks of the infected goods. Hyams said that the operation's mastermind, Dr. Luke P. Blackburn, who he met in Halifax, told him that trunk "Big Number 2" "will kill them at sixty yards distance." Hyams testified that he refused to deliver an infected trunk "as a donation to President Lincoln," but did place the others in channels of distribution near concentrations of Union soldiers. For his work, Hyams testified, he received congratulations from Clement Clay. Some of the infected goods were auctioned near a Union base of operations by New Bern, North Carolina shortly before nearly 2,000 citizens and soldiers died there during a yellow fever outbreak. Bingham attributed the epidemic to the Confederate plot, not knowing (as was discovered in 1901) that mosquitoes--not people--cause yellow fever.

The Assassination Conspiracy's Link to the Canadian Clique and Jefferson DavisThe prosecution offered evidence to show that the conspiracy against Abraham Lincoln and other high government officials began sometime after the battle at Gettysburg--probably in the summer of 1864. Witness Sanford Conover (whose real name later turned out to be Charles Durham) reported Confederate Secret Service head Jacob Thompson as identifying the goal of the conspiracy as to "leave the government entirely without a head" by killing not only Lincoln, but also Vice President Johnson, Secretary of War Stanton, Secretary of State Seward, and General Grant. Conover, a former employee of the Rebel war Department, in what is widely believed to be perjurious testimony quoted Thompson as saying there was "no provision in the Constitution of the United States by which, if these men were removed, they could elect another President."

Henry Van Steinacker, a Union soldier convicted of desertion, testified that while on a long horse ride in Virginia with John Wilkes Booth in late summer of 1863 Booth opined, "Old Abe must go up the spout [be killed], and the Confederacy will gain its independence." (Steinacker, whose real name was Hans Von Winklestein, was released from prison shortly after his testimony, causing many to question his credibility.) Several witnesses testified that by the fall of 1864 a proposal to assassinate or abduct Union leaders, presumably made by Booth, was under active review by Confederate officials in both Canada and Richmond. Witnesses told of frequently seeing Thompson and Clement Clay in Montreal in the company of of conspirators John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and Lewis Powell.

Richard Montgomery, a Union double agent in Canada, testified (perjuriously, again, according to many historians) that Thompson as saying in January 1865 that it would be a "blessing" to "rid the world" of Lincoln, Johnson, and Grant. Montgomery testified that Thompson revealed that a "proposition" had been made by a group of "bold, daring men" to do just that.

Samuel Chester testified that beginning in November 1864 Booth tried to recruit his participation in a plot to abduct Lincoln and take him to Richmond, where he would be held until he could be exchanged for Confederate prisoners-of-war. Initially, it seems, the proposal (either to abduct or assassinate Lincoln) was rejected in Richmond, as Montgomery quotes Montreal clique member Beverly Tucker as complaining that it was "too bad that they boys had not been allowed to act when they wanted to."

Henry Finegas testified as to overhearing a conversation, made in "a low tone of voice" in Montreal in mid-February between Confederate clique members George Sanders and William Cleary:

Sanders: If the boys only have luck, Lincoln won't trouble us much longer.

Cleary: Is everything going well?

Sanders: Oh, yes. Booth is bossing the job. Key government witness Louis Weichmann-- a boarder at Mary Surratt's and a friend of Booth, Powell, and other conspirators--testified that on March 27, 1865 John Surratt visited Richmond and conferred with Confederate Attorney General Judah Benjamin and President Jefferson Davis. Surratt returned from Richmond to Washington, before heading north out of the Capital on April 3. On April 6, John Surratt arrived in Montreal carrying with him--according to the prosecution's theory--final approval for Booth's assassination attempt. Sanford Conover, a former employee of the Rebel War Department, testified that he was present at a meeting in the Montreal hotel room of Jacob Thompson when dispatches brought by Surratt from Richmond, including a letter in cipher from Jefferson Davis, were discussed. According to Conover's testimony--strongly attacked by latter-day supporters of Davis--"Thompson laid his hand [on the dispatches from Richmond] and said, "This makes the thing all right." A Canadian banker testified that Jacob Thompson withdrew $184,000 from the over $600,000 in his private Montreal account on April 6. Special Judge Advocate John Bingham, in his summation for the government, found the evidence against Jefferson Davis damning:What more is wanting? Surely no word further need be spoken to show that John Wilkes Booth was in this conspiracy; that John Surratt was in this conspiracy; and that Jefferson Davis and his several agents named, in Canada, were in this conspiracy....Whatever may be the conviction of others, my own conviction is that Jefferson Davis is as clearly proven guilty of this conspiracy as John Wilkes Booth, by whose hand Jefferson Davis inflicted the mortal wound on Abraham Lincoln. Bingham found further confirmation of Davis's guilt in a letter of October 13, 1864, discovered in the possession of Booth after the assassination of Lincoln. The ciphered letter, which notified Booth that "their friends would be set to work as he had directed," was proven to have been typed on a cipher machine recovered from a room in Davis's State Department in Richmond. Finally, Bingham found incriminating Davis's reaction in North Carolina upon learning of the President's assassination: "If it were to be done at all, it were better that it were well done."Evidence Concerning the Eight PrisonersAs each of the eight defendants played different roles in the assassination conspiracy, the evidence of guilt varied as well. The connection of Lewis Powell and David Herold to the conspiracy was clear almost beyond question, while the case against others--notably Dr. Samuel Mudd and Mary Surratt--was considerably more circumstantial, but nonetheless ultimately convincing.

Many trial observers found Lewis Powell, the handsome young defendant who maintained a posture of studied indifference to the proceedings, to be the most intriguing of the prisoners. The case against Powell was overwhelming. Even Lewis Powell's attorney, William Doster, recognized his complicity in the plot was beyond question. Identified as Seward's attacker by Seward's servant, found with blood on his shirt and the initials of John Wilkes Booth in his boots, and identified by Louis Weichmann as the man who called himself "Wood" and who--claiming to be a Baptist preacher and wearing a large false mustache-- frequently called at Mary Surratt's home, where he would sometimes engage in two or three hour private conversations with Booth and John Surratt, Doster was left to argue that Powell's life should be spared because he suffered from a fanaticism that bordered on insanity. "I say he is the fanatic, and not the hired tool," Doster told the Commission. "He lives in that land of imagination where it seems to him legions of southern soldiers wait to crown him as their chief commander." Doster said that when he asked Powell why he did it, he replied, simply, "I believed it was my duty." Doster described Powell as an innocent farmboy turned assassin by circumstances beyond his control: "We know now that slavery made him immoral, that war made him a murderer, and that necessity, revenge, and delusion made him an assassin." Doster ended his remarkably eloquent plea (but obviously hopeless) for Powell's life by asking the Commission to "Let him live, if not for his sake, for our own."

David Herold's position was equally precarious. Apprehended with the President's assassin and having bragged about the crime--telling one prosecution witness, Willie Jett, as he crossed the Rappahannock, "We are the assassinators of the President"--Herold's attorney, Frederick Stone, placed whatever slender hopes for saving Herold's life on his client's simple-mindedness and youth. One defense witness called Herold "a light and trifling boy" who was "easily influenced," while a second said of Herold:"In mind, I consider him about eleven years of age." Stone argued to the Commission that Herold "was only wax in the hands of a man like Booth."

Unlike Lewis and Herold, the guilt of Ford's Theatre stagehand Edman Spangler was not beyond question, but prosecutors presented several witnesses who testified that Spangler played a critical--although minor--role in Booth's escape from the theatre. Joseph Burroughs, better known as "Peanuts," a Ford's employee given the duty of guarding the stage-door during plays, testified that between nine and ten o'clock on the night of the assassination Spangler "told me to hold [Booth's] horse." Burroughs told the Commission that when he replied that "I had to go in to attend my door" Spangler said he should hold the horse anyway and "if there was any thing wrong to lay the blame on him." Other witnesses reported seeing Booth around seven-thirty that evening, standing at the back door of the theatre and holding his horse and calling for "Ned" Spangler. John Sleichmann, a property man for the theatre, testified that he saw Booth enter the back door of the theatre and ask Spangler, "Ned, you'll help me all you can, won't you?" According to Sleichmann, Spangler replied, "Oh, yes." Joseph Stewart, a theatergoer with a front orchestra street who ran after Booth across the stage yelling, "Stop that man!," testified that he was "satisfied" that Spangler was the person he saw near the rear door who was in a position to block Booth's exit if he had been so inclined. Finally, John Miles, a Ford's employee, testified when he asked Spangler who it was he saw holding Booth's horse before his escape, Spangler replied, "Hush, don't say anything about it." Spangler's defense attorney, Thomas Ewing, argued that while the prosecution evidence might suggest Spangler agreed to assist Booth on April 14, it failed to prove that Spangler was aware of Booth's guilty purposes in requesting his assistance.

A letter from Samuel Arnold to Booth, dated March 27, 1865, and found in Booth's possession after the assassination provided compelling evidence that Arnold had willingly agreed to participate in the original plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond. In his letter, Arnold wrote that "None, no, not one were more in favor of the enterprise than myself." Arnold's attorney, Walter Cox, argued that Arnold "backed out from this insane scheme of capture" and it was "abandoned somewhere about the middle of March." Arnold, he argued, left Washington for Maryland about March 20 and that there "is no evidence that connects" Arnold with the "dreadful conspiracy" of assassination. Cox told the Commission that Arnold's participation in the "mere unacted, still scheme" of abduction was "wholly different from the offense described in the charge."

Michael O'Laughlen, who boarded at the same home in Washington as Arnold, might qualify as the most forgotten of the eight conspirators on trial. The key evidence against O'Laughlen also links him to Booth's abandoned plan to abduct Lincoln. On March 13, Booth sent to O'Laughlen, then in Baltimore, a telegram from Washington: "Don't fear to neglect your business. You better come at once." Twelve days later, Booth sent another telegram to O'Laughlen: "Get word to Sam. Come on, with or without him, Wednesday morning. We sell that day for sure. Don't fail." Prosecutors suggested that the "business" referred to in Booth's telegraph was the kidnapping of Lincoln and that the "Sam" referred to in the second dispatch was Samuel Arnold. Bernard Early, an acquaintance of O'Laughlen's, testified that he rode into Washington with O'Laughlen from Baltimore on the day before the assassination. Early said that the next day he waited with O'Laughlen at the National Hotel, where Booth had taken a room, for forty-five minutes before sending "up some cards to Mr. Booth's room for O'Laughlen" and leaving. Most incriminating, perhaps, was the testimony of Major Kilburn Knox, who testified that about ten-thirty on the night of April 13 O'Laughlen, wearing black clothes and a slouch hat, entered the home of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and inquired of the Secretary's whereabouts. Knox said that O'Laughlen remained in the hall for a few minutes before being asked to leave. Two other witnesses also reported seeing O'Laughlen at the Secretary's home. Defense attorney Walter Cox argued that the prosecution witnesses were mistaken, and that on the night in question O'Laughlen innocently strolled the streets of the nation's capital enjoying the "night of illumination," the celebration of the Union victory that saw every public building in Washington lit with candles. Cox also argued that the evidence showed persuasively that O'Laughlen did nothing to further the assassination on the night of the fourteenth, which he spent drinking at Lichau House before departing for Baltimore the next day.

The prosecution argued that Booth assigned George Atzerodt the job of killing Vice-President Andrew Johnson. Colonel W. R. Nevins testified that on April 12 at the Kirkwood Hotel in Washington, Atzerodt asked him where he might find Vice President Johnson. Police investigator John Lee testified that he searched Atzerodt's room at the Kirkwood (the same hotel that the Vice President was then staying at) on the day after Lincoln's assassination and discovered under a loaded revolver, a bowie knife, a map of Virginia, three handkerchiefs, and a bank book of John Wilkes Booth. The prosecution also showed that Atzerodt had met frequently with Booth in front of the Pennsylvania House in Washington. John Fletcher, an employee of J. Naylor's livery stable testified that on April 14 Atzerodt showed up at the stable with co-defendant David Herold, bringing with them a dark-bay mare. Another witness told of Atzerodt's late night check-in (after midnight) on the night of Lincoln's assassination at the Pennsylvania House, his leaving again and returning around two, and then his checking out of the hotel between five and six in the morning.

George Atzerodt's attorney, Captain William E. Doster, argued that his client's cowardice made it unlikely that he played any significant role in the assassination conspiracy. "I intend to show," Doster told the Commission, "that this man is a constitutional coward; that if he had been assigned the duty of assassinating the Vice President, he could never have done it; and that, from his known cowardice, Booth probably did not assign to him any such duty." Doster presented defense witnesses who described Atzerodt as a "notorious coward"and as a man "remarkable for his cowardice."

President Andrew Johnson considered Mary Surratt the keeper of "the nest that hatched the egg." Numerous witnesses reported Booth, Herold, Powell and other conspirators as frequent visitors to Surratt's boarding house in Washington. Evidence of association with conspirators would, of course, not by itself sustain a conviction. Prosecutors produced witnesses who showed convincingly that Surratt lied when she told authorities, when asked if she knew Lewis Powell, "Before God, sir, I do not know this man." The most incriminating evidence against Surratt came, however, from two witnesses, Louis Weichmann and John Lloyd. Weichmann, a boarder in Surratt's home, testified that Booth gave him $10 on the Tuesday before the assassination which he was to use to hire a buggy to take Surratt to her tavern in Surrattsville to collect--according to Surratt--a small debt. Weichmann also told the Commission that on the day of the assassination, Mary Surratt sent Weichmann to hire a buggy for another two-hour ride to Surrattsville. Surratt and Weichmann arrived sometime after four at Surratt's tavern. According to Weichmann, Surratt went inside while Weichmann waited outside or spent time in the bar. Surratt remained inside about two hours. Between six and six-thirty, shortly before the began their return trip to Washington, Weichmann saw Surratt speaking privately in the parlor of the tavern with John Wilkes Booth. At nine o'clock, Weichmann saw Booth again when he came to the Surratt home for a last time. After the visit, according to Weichmann, Surratt's demeanor changed--she became "very nervous, agitated and restless."

The most damning evidence of all against Surratt came from Surrattsville tavern keeper John Lloyd. Lloyd told the Commission that five to six weeks before the assassination John Surratt, David Herold, and George Atzerodt came to Surrattsville to drop off at his tavern two carbines and ammunition. Lloyd testified that three days before the assassination, Mary Surratt told him that "the shooting irons" left at his place by the men weeks ago would be needed soon. Then on the day of the assassination, Surratt again brought up the subject, according to Lloyd:

On the 14th of April I went to Marlboro to attend a trial there; and in the evening, when I got home, which I should judge was about 5 o'clock, I found Mrs. Surratt there. She met me out by the wood-pile as I drove in with some fish and oysters in my buggy. She told me to have those shooting-irons ready that night, there would be some parties who would call for them. She gave me something wrapped in a piece of paper, which I took up stairs, and found to be a field-glass. She told me to get two bottles of whisky ready, and that these things were to be called for that night.

Surratt's attorney, Frederick Aiken, argued that Lloyd's evidence should be disbelieved because he was "a man addicted to the excessive use of intoxicating liquors" and was motivated to "exculpate himself by placing blame" on Mary Surratt.

The prosecution based its case against Dr. Samuel Mudd on the testimony of several witnesses that suggested a much closer relationship between the doctor and John Wilkes Booth--and other conspirators-- than Mudd would admit. Several witnesses testified that they saw Mudd with John Wilkes Booth on November 13, 1864 in Maryland. Witnesses said that Mudd during that November visit helped Booth buy a horse--a horse that he most likely used in his flight from Ford's theatre. Louis Weichmann testified that in late December he was walking with John Surratt near the National Hotel in Washington when Mudd, walking with Booth, called out "Surratt! Surratt!" According to Weichmann, the three men later excused themselves for private conversation over what Mudd claimed to be Booth's interest in purchasing real estate in Maryland. Attorney Marcus Norton testified that in early March, when he was in Washington to argue a case before the Supreme Court, a man he now recognized as Mudd excitedly burst into his room at the National Hotel. Norton said the man apologized for his entry, saying that he thought the room belonged to a man named "Booth"--who actually had rented the room directly above Norton's. A minister, William Evans, testified that he saw Mudd go into the home of Mary Surratt in early March of 1865. The evidence concerning Booth's prior dealings with Booth strongly suggested that Mudd lied to investigators when he denied having recognized Booth when he treated his broken leg on April 15. Alexander Lovett told the Commission that Mudd appeared suspicious from the start of his investigation: "When we first asked Dr. Mudd whether two strangers had been there, he seemed very much excited, and got pale as a sheet of paper and blue about his lips, like a man frightened at something he had done."

Prosecutors also produced witnesses who testified concerning certain statements Mudd allegedly made about President Lincoln and the federal government. Daniel Thomas testified that he heard Mudd state in early 1865--whether jokingly or not, he couldn't tell--that "the President, Cabinet, and other Union men" would "be killed in six or seven weeks." Mary Simms, a former slave of Mudd's, testified that during the war Mudd complained that Lincoln "stole [into office] at night, dressed in women's clothes" and if "he had come in right, they would have killed him." Another slave, Milo Gardiner, testified that he overheard a friend of Mudd's, Benjamin Gardiner, tell Mudd that "Lincoln was a goddamned old son of a bitch and ought have been dead long ago" and that Mudd replied "that was much of his mind."

Mudd's attorney, Thomas Ewing, argued that Mudd's only prior encounter with Booth had been the one in November and that all the later alleged meetings were fabrications of prosecution witnesses. Ewing contended that it was no crime to fix a broken leg, even if it were the leg of a presidential assassin and even if the doctor knew it was the leg of a presidential assassin. Ewing argued that the prosecution must prove more: that Mudd actually furthered the conspiracy in some way. Prosecutors responded by arguing that the evidence showed more than the defense admitted. They contended that Mudd furthered the conspiracy by, for example, pointing out to Herold the route that he and Booth should take upon leaving his farm.

SENTENCES AND EXECUTIONSOn June 29, 1865, the Military Commission met in secret session to begin its review of the evidence in the seven-week long trial. A guilty verdict could come with a majority vote of the nine-member commission; death sentences required the votes of six members. The next day, it reached its verdicts. The Commission found seven of the prisoners guilty of at least one of the conspiracy charges, and Spangler guilty of aiding and abetting Boooth's escape. Four of the prisoners (Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold) were sentenced "to be hanged by the neck until he [or she] be dead." Samuel Arnold, Dr. Samuel Mudd and Michael O'Laughlen were sentenced to "hard labor for life, at such place at the President shall direct." Edman Spangler received a six-year sentence.

The Commission forwarded its sentences and the trial record to President Johnson for his review. Five of the nine Commission members, in the transmitted record, recommended to the President--because of "her sex and age"--that he reduce Mary Surratt's punishment to life in prison. On July 5, Johnson approved all of the Commission's sentences, including the death sentence for Surratt.

The next day General Hartrandft informed the prisoners of their sentences. He told the four condemned prisoners that they would hang the next day.

Surratt's lawyers mounted a frantic effort to save their client's life, hurriedly preparing a petition for habeas corpus that evening. The next morning, Surratt's attorneys succeeded in convincing Judge Wylie of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia to issue the requested writ. President Johnson quashed the effort to save Surratt from an afternoon hanging when he issued an order suspending the writ of habeas corpus "in cases such as this."

Shortly after one-thirty on the afternoon of July 7, 1865, the trap of the gallows installed in the courtyard of the Old Arsenal Building was sprung, and the four condemned prisoners fell to their deaths. Reporters covering the event reported that the last words from the gallows stand came from George Atzerodt who said, just before he fell, "May we meet in another world."

EPILOGUE AND THE CONSPIRACY AS NOW UNDERSTOODIn the summer of 1867, John Surratt, having been captured in Egypt, faced trial in a civilian court for having participated in a conspiracy to assassinate the president. The jury was unable to reach a verdict, with eight jurors voting "not guilty" and four voting "guilty." In August, 1867, Surratt was released from prison. Three years later he began a public lecture tour describing his association with the conspirators and proclaiming his innocence.

Military personnel escorted Dr. Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold to Fort Jefferson in Dry Tortugas, Florida. Two years later, a yellow fever epidemic swept the prison, killing O'Laughlen and the prison's doctor, among many others. Upon the death of the prison doctor, Mudd assumed duty as chief medical officer at the prison. On March 1, 1869, Mudd and the other three imprisoned conspirators received an eleventh-hour presidential pardon from President Johnson.

The last surviving convicted conspirator was Samuel Arnold, who died in 1906 after writing a detailed confession of his role in the conspiracy to kidnap President Lincoln.

Over the years, critics have attacked the verdicts, sentences, and procedures of the 1865 Military Commission. These critics have called the sentences unduly harsh, and criticized the rule allowing the death penalty to be imposed with a two-thirds vote of Commission members. The hanging of Mary Surratt, the first woman ever executed by the United States, has been a particular focus of criticism. Critics also have complained about the standard of proof, the lack of opportunity for defense counsel to adequately prepare for the trial, the withholding of potentially exculpatory evidence, and the Commission's rule forbidding the prisoners from testifying on their own behalf. The critics have a point: The 1865 trial of the Lincoln conspirators did fall short of commonly accepted norms of procedure and the verdicts--by modern standards--seem harsh.

There does seem little question, however, that four of the convicted conspirators participated--in ways either large or small--in Booth's plan to assassinate key federal officials. Lewis Powell clearly attempted to stab to death Secretary Seward. David Herold, Dr. Samuel Mudd, and Edman Spangler aided Booth's escape from Washington. Herold and Mudd provided aid to Booth with full knowledge of his crime--and Spangler most likely did as well.

The four other convicted conspirators--and Jefferson Davis--undoubtedly supported at least Booth's original plan, to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond. George Atzerodt, in a confession made shortly before he was hanged, admitted to have willingly agreed to play an important role in the planned abduction, but claimed not to have supported the assassination--and to have first heard of the plan to assassinate Lincoln just two hours before Booth fired his fatal shot. Arnold also admitted his initial willingmess to participate in the kidnap plot. The evidence with respect to O'Laughlen's and Mary Surratt's complicity in the scheme is only slightly less compelling. Recent scholarship has strengthened the already strong evidence that approval for the kidnapping came directly from Jefferson Davis. William Tidwell's Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln shows that large numbers of Confederate troops had massed in March of 1865 in the northern neck of Virginia along what must have been a planned route to take Lincoln to Richmond. Apart from a planned abduction of Lincoln, there was no plausible strategic reason for their placement in that area.

The prosecution fairly can be faulted for intentionally obscuring the fact that there were two conspiracies involving Lincoln in 1865: the original abduction plan, developed in the fall of 1864 and supported by all eight conspirators and top Confederate leadership, and Booth's assassination plan, conceived only after the original plan fell through when Lincoln cancelled plans to attend a play at the Campbell Hosptial on the outskirts of Washington on March 17. (The plan had been to intercept the President's carriage as it returned from the matinee performance.)

After the failure of the March 17 plot, and abandonment as infeasible of another plot to kidnap Lincoln at Ford's theatre, Booth's thoughts turned to assassination. Shooting Lincoln seems to have been on Booth's mind by April 7 when, after some hard drinking with his friend Samuel Chester in New York, Booth slammed the table and said, "What a splendid chance I had to kill the President on the fourth of March!" Booth's April 7 visit to New York was one of several in the weeks leading up to the assassination, leading some historians to speculate that New York was the location of his Confederate Secret Service control--possibly Confederate underground insider Roderick Watson. George Atzerodt's confession revealed that Booth learned during his last New York visit of a plot by his Confederate associates to kill the President by blowing up the Executive Mansion: "Booth said he had met a party in New York who would get the prest. [president] certain. They were going to mine the end of the pres. [president's] House. They knew an entrance to accomplish it through." The dispatch from Richmond that reached Montreal on April 6, carried by John Surratt and Sarah Slater, most likely authorized activation of the bombing plot. The capture of the Confederate explosives expert assigned the task of planting the bombs the Executive Mansion, Thomas Harney, on April 10 must have prompted Booth to begin planning his own attempt on Lincoln's life. By April 11, his mind was made up. After to listening to Lincoln speak from the balcony of the Executive Mansion on his plans for reconstruction, Booth--according to Thomas Eckert who interviewed Powell in prison--turned to Lewis Powell and said, "That is the last speech he will ever make!" By April 13, Booth was casing both Ford's Theatre and Grover's National Theatre, anticipating that the President would soon take a night out--his last.

At Garrett's farm, Colonel Everton Conger found on the body of John Wilkes Booth a small red book, which Booth kept as a diary. In an entry written sometime between the assassination and his capture, Booth wrote: "For six months we had worked to capture, but our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done. But its failure was owing to others, who did not strike for their country with a heart." The prosecution did not introduce Booth's diary into evidence in the 1865 trial. In 1867, it turned up in a forgotten War Department file with eighteen pages missing.

Note:

**In Booth's diary, he insisted he shouted "Sic semper tyrannus!" ("Thus to tyrants!") before he shot Lincoln. Most accounts of the assassination report that Booth broke his leg upon landing on the stage. Eyewitnesses, however, did not report that Booth limped across the stage and one historian, Michael Kaufmann, argued that Booth injured his leg in his hurried attempt to mount his horse after exiting Ford's theater.

*************************************************************************************

FOR PERSONS DESIRING ANOTHER OVERVIEW OF THE CONSPIRACY AND THE EFFORTS TO TRACK DOWN AND TRY THOSE INVOLVED, A LINK TO THE ACCOUNT OF H. L. BURNETT--ONE OF THOSE WHO SERVED WITH THE MILITARY COMMISSION THAT TRIED THE CONSPIRATORS--IS PROVIDED:

Account of assassination, investigation, trial and aftermath by Brig. Gen. H.L. Burnett

The Conspiracy Trial: Questions for Discussion

|